Cape Verde – Boa Vista

Roughly circular in shape, the island of Boa Vista lies about 20 miles south of Sal. On a clear day one can look across from Santa Maria and see the barren hills of Boa Vista’s north coast; but clear days are few and far between in the Cape Verdes.

Paradise Island

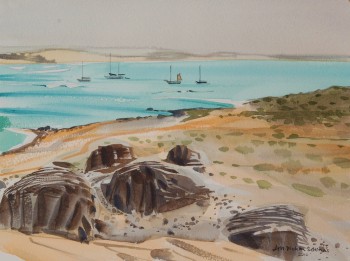

The first time we visited Boa Vista we fell in love with the place. We spent a month anchored in the big bay which eats into the island’s west coast; a month lying off a pristine white beach which was frequented only by ourselves and by nesting turtles; a month on blue-green waters which we shared only with the fishermen passing by in their lateen-rigged boats.

In the mouth of the bay, towards its northern jaw, there lies a little islet known as Ilha Sal Rei – the island of the salt king – and we spent most of our time anchored in its lee. Every now and then, feeling the need for some variety, we moved south, to the “mainland” shore and dropped the hook off a tall brick chimney – an intriguing feature of the landscape, being the only man-made thing in view, when we looked to the south.

To the north lay the metropolis, as we named it. And between the metropolis and our anchorage lay a mile of shallow water cluttered by coral heads. Rather than pick our way amongst them with the dinghy – and rather than go to the effort of rowing upwind – we decided to land on the beach, adjacent, and walk. This proved to be quite an adventure.

Equipped with a rucksack in which to carry the shopping and a back-pack in which to carry our infant daughter, we set off; but the waves dumping on the beach proved to be bigger than we had realised, and as the dinghy touched the sand one little monster grabbed the bow, hurled it high in the air, and tipped rusksack, back-pack, both toddlers, and their mother and father out into the surf.

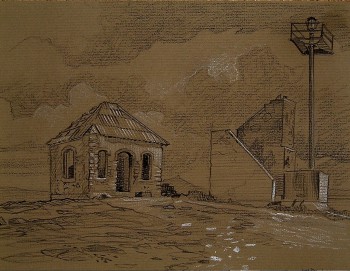

Ashore, at the end of our mile-long saunter along the sand, we found a half-derelict village posing as the capital city. Sand swept down its broad empty streets and over the adjacent salt-pans.

There were no shops, and the vendors sitting on the kerb in the huge empty praҫa were even more shabby than their two week-old imported vegetables.

Children ran to their schoolroom window to watch the shiny white people go by.

We saw no cars, nor even any aluguer pick-up trucks such as were used for taxis in the other islands.

Visiting Boa eighteen years ago we felt that we had travelled back, in our floating time-machine, to the world of the 18th century European peasant. And – having scant knowledge, at that time, of the nation’s politics – we couldn’t understand why this wonderful place was ours, and ours alone.

“If I were a developer I’d buy a slice of this beach. Just look at it! It’s a gold mine!”

Sorry, but you’ve missed the boat

Ten years passed before we went back to Boa Vista. Having been brought up on tales of a paradise island, where they used to toddle in the surf and frolic in the dunes, the kids wanted to see the place anew; and so we detoured, during a journey north from South Africa to the Med, for the express purpose of showing them Our Favourite Place in All the World.

Hearts brimming over with excitement, we sailed into the bay… and there it was: a ruddy great hotel, defacing that magnificent arc of white sand!

And not just one hotel. No, there were others under construction; other concrete cliffs marring the beauty of the bay, like graffiti carved on the smooth trunk of a beech tree.

And that was not all.

Tucked behind the reef which separates the bay from the town – in the anchorage which was once ours, alone – we found ten or fifteen other yachts. A mere sprinkling in a bay of that size, but still it was not quite what we had planned…

And when we strolled along the beach (amongst the tourists, clad in their beach-wear) and arrived at the town, we found that it had sprawled. Besides the new concrete apartments on the edge of town there was now an African ghetto where immigrant labourers, brought in to build the hotels, lived in squalor alongside the locals. Scarcely more well-to-do than when we saw them last, and little better-off than their new fellow-citizens, the Bubistans nevertheless held the Africans in utter contempt and an uneasy peace hovered over the place.

Ambling southwards again, along the beach, we came to the sand dunes and to the old chimney… and to a concrete and glass conurbation with fancy Moorish parapets.

Behind the hotel we rediscovered a sandy trail which we used to follow, across the dusty spartan landscape, to get to the nearby village of Rabil.

Beasts of burden

In Rabil we once watched a woman making beautiful water jars, squeezing the soft clay from her fingers as she built up the walls. Her kiln was a bonfire which she stoked, for three days and nights, on the rocky ground behind her house.

In Rabil we had seen men and boys gathering twigs and sticks for the fire; piling a donkey high under a burden of straw and twigs until it seemed to be a four-legged bush. And we had met women and girls – girls barely ten years of age – whose days were spent walking to and fro between their stone cottages and the village well; whole lifetimes spent walking to and fro fetching water. Whole lifetimes spent as a beast of burden.

Behind and below the village of Rabil runs a dry ribeira where – 18 years ago – the people were doing their best to raise a few sticks of maize and some beans, but in Boa Vista even this labour – the oldest profession of man, and the one which truly sets him apart from the beasts – was fraught with difficulty. Marching relentlessly down the gorge from within the island came a wall of white sand: a magnificent dune but a deadly one, for it was determined to bury everything in its path.

Nowhere in our travels have we ever met a people whose lives are harder than was the life of a Bubistan peasant, 18 years ago; and it struck us that this was also the only place in the Cape Verdes where the people were less than friendly towards us. Not that anyone was remotely hostile, but nor did they rush up to greet us with smiles on their faces – as they used to do in all the other islands – or invite us into their homes. They simply glanced at us – in utter astonishment at times – and then they bowed their heads again and got on with their toil. (I remember one time we knocked on the door of a certain house which, we had been told, was the abode of the village basket maker. When he opened the door the man nearly fell over backwards, such was his astonishment at seeing our white faces!)

We noted also that there was a complete dearth of laughter in these villages. There was no joy anywhere – except in the hearts of the fishermen, fishermen being able to procure a meal without needing to break their backs and their spirits too.

Whereas the people of the other islands were living in poverty but were enjoying themselves, none the less, the Bubistan farmers were desperate. They were fighting, on a daily basis, against some of the most hostile conditions that nature can throw up, and they were down on their knees. Their existence held no time or space for fun or even for thought. Moreover, I suspect that their nutrition was so poor that they lacked the energy to do anything which might improve their lot. They had been reduced to the state described by the Welsh poet, R.S. Thomas: “Enduring like a tree under the curious stars.”

But that was back in 1994. Ten years later, things had changed. Now the people were no longer dependent on the fruits of the soil. Tourism was bringing money into the island and although most of it was going to the rich Italians who owned the all-inclusive hotels, some was filtering down to the rightful owners of that perfect white sand beach; a beach where they – the islanders themselves – had never before had the time to play.

Wouldn’t it be nice if, someday, somewhere, someone who already has more than enough money for his own needs discovered a beautiful, pristine beach and an impoverished people and decided to set up a well-run, environmentally sensitive hotel in the name of those peasants…?

Progress has a price

Anyway… back in 2004 the life and lot of the average Bubistan had improved markedly. The men no longer scoured the land all morning for fuel, or toiled in that barren valley, and the women no longer wasted their lives fetching water. If they didn’t smell of money the people seemed, at least, to have had the burden of poverty taken from their shoulders; and if they had, as yet, only peeped through the window and caught a confusing glimpse of luxury they had, at least, been given the gift of leisure time.

Adults and children alike, most of the islanders now wore clean, smart T-shirts. The fishermen’s lateen-rigged fishing boats were now equipped with outboard motors. There were bars in the village of Rabil – seemingly, the people now had a little bit of money to spend on grog – and the local pottery now boasted a gas-fired kiln. We noted, too, that there were now taxis and mini-buses on the roads, so the people were now able to travel with ease; but we also observed that their attitude towards tourists had not changed – they still looked straight through us – and nor did they appear to be overflowing with joy and happiness. Perhaps the transition from 18th to 21st century has been rather too swift; or perhaps the knowledge that their island has been sold out to foreign investors is too painful.

In 2010 we visited Boa Vista again and were relieved to find that there are no high-rise hotels on the beach which embraces that huge bay on Boa Vista’s west coast. However we hear that there are major developments in other places. The island now has an airport with a runway big enough to accommodate international flights.

Effectively it would seem that the erstwhile sleepy and backward isle of Boa Vista has been sold out for the sake of enriching the country as a whole.

From the Point of View of a Visiting Yachtsman

Of course, from the point of view of a selfish tourist, wanting to photograph picturesque kids in scruffy patched dresses, and donkeys laden with wood, and old men with hoes, Boa Vista is ruined… but we are not here to discuss that aspect of things; we are here to talk about the anchorage.

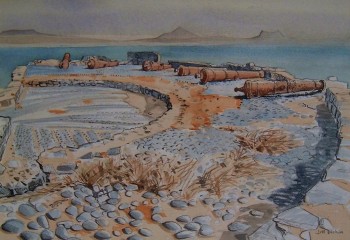

The Town Quay

Fifteen years ago there was only one place for the seafarer to go in Boa Vista, and that was the bay on the west coast. This is where we anchored, and this is where the inter-island ferry and the little cargo ships used to anchor. Vegetables, crates of beer, dry goods, and passengers too, were all disembarked into the fishing boats – little open boats hardly bigger than our own tender – which shuttled to and fro between the vessels and the town quay, a mile away across the reef. We’ve even seen horses being landed in this way (one to each boat).

Now, the town has its own small quay, and the ships can go alongside. Yotties, too, can go alongside the quay (to take water) and they can also anchor in the lee of this new facility, approaching the town around the northern end of the off-lying islet of Sal Rei. We haven’t been in there with Mollymawk, so I can’t comment on the holding, or the depths, or on the attitude of the fishermen who keep their boats in this vicinity, but I will say that, during the winter months at any rate, the approach is likely to be quite exciting. I’ve stood on islet and watched breakers rolling in, in constant succession, along the channel.

The Anchorage

Early versions of the RCC Cruising Guide described Boa Vista as a dangerous place, best given a good offing. This is rather unfair; but nor is the place a perfect haven of tranquillity. In the winter months the anchorage is apt to be very rolly, and when the swell is up it can very suddenly become a very dangerous trap.

The approach to the bay is straightforward. All you need to do is keep well clear of English Reef. During the winter months this usually breaks and is very visible, but in the summer, when the swells are down, the dragon lurks unseen beneath the surface. I don’t know exactly how much water there is on the reef, but I’ve kayaked over it – timing my passage carefully, between the rollers – and have touched it with my paddle blade.

Back in the 90s we used to anchor in various places throughout the bay, but our favourite spot was behind a little reef which forms a nook on the eastern side of Ilha Sal Rei. We used this place again in 2004, but when we visited in 2010 we found it impossible to set the hook. A thorough exploration with a mask and snorkel showed that the sand has been scoured away leaving only a thin layer on top of the rock.

Turning our attention to the area outside this little nook – to the stretch of water between the islet and the main island – we wondered why all of the boats were grouped tightly together. It transpired that they were all clinging to the one small patch of sand which was deep enough to allow a Bruce or a Spade to get a grip! 16 years ago there were some magnificent dunes on the shore in this vicinity. 10 years ago they had vanished. Seemingly, they walked into the sea and have now been ferried thence, leaving nothing but rock.

On our last visit to Boa Vista (February 2010) the yachts were surging to and fro like panic stricken horses tugging at their tethers. The motion was so violent that some friends aboard a narrow but full-keeled 40-footer were thrown out of their bunks.

When the swells really get up the waves break in the area directly south of this anchorage and the gap between English reef and the islet grows narrower, until… But don’t wait around to see if it closes altogether; when things begin to look iffy you need to escape while you still can. (The locals assure us that the entrance to the bay is sometimes entirely swept by breaking waves.)

Friends who anchored here in February of 2011 had to get out in the middle of the night, and they are not the first to have been in this position.

Essentially, this is a summer anchorage; and even then, it’s best to remain on your toes at all times.

Photos and paintings by Jill Dickin Schinas.

For more information about the Cape Verde islands, take a look at our other recent articles about the archipelago:

- General info:

- Sal

- São Vicente

- Boa Vista