Cape Verde Islands – History and Culture

Cruising notes given in good faith, but not to be taken as gospel.Inasmuch as it consists of just a few fragments of rock, flung far away from the continent and strewn across almost two hundred miles of ocean, the Republic of Cape Verde is superficially similar to the Canaries or the Azores; but in reality, geographic structure and a similar sort of lingo are pretty much the only things that this archipelago holds in common with those other two places.

Desert Islands

Cape Verde is made up of ten main islands plus five islets and numerous rocky bits and pieces. Of those ten principal islands only nine are inhabited, the other one having no freshwater.

If it comes to that, one of the others is also entirely arid – until the latter years of the 20th century its supply of aqua vita came from the neighbouring island – and a third is so dry that until recent times it could support only a handful of fisher-folk and salt-makers.

Yes, though it lies far out in the ocean, with the wet stuff on every hand, this country is actually an outpost of the Sahara desert!

Times change, however; and right now, in the Cape Verdes they are changing very fast indeed. The modern world has finally noticed the sleepy island nation and is in the process of hauling it out of the 18th century and into the 21st. In the course of these events the last of those three islands, which once seemed worthless, has become the country’s “biggest earner”; and the second island – waterless but inhabited – is now home to the nation’s second city. The first of the three islands has been declared a nature reserve, and no one may go there at all, but whether this status will protect it from the developers’ greed remains to be seen.

Finders Keepers

The Cape Verdes lie off Cap Vert, and that’s how they got their name. The archipelago itself was never very verdant. The Portuguese settlers responsible for establishing the first colony here chose the site which they considered to be “the least unpromising”: a small oasis on the seaward edge of a rather desiccated landscape.

So, contrary to what most people believe, the view which greets the yachtsman as he approaches Sao Nicolau or Sal is probably not so very different from the one which startled Antoni de Noli 550 years ago.

So far as we know, Noli and his fleet – trundling down the coast of Africa in 1456 – were the first people ever to lay eyes on any of the Cape Verdes. Certainly nobody had ever tried living here before the Portuguese arrived; or if they did they left behind not one single human bone, not one hut circle, nor any other scrap of evidence. The people who live here now are descended from Portuguese peasants seduced by the promise of free land and from West African men and women who were brought here to be sold.

This is where it all began

Slavery was, indeed, the new colony’s chief raison d’etre. Attempts were made to produce grapes and sugar – and these two crops are still grown here in a very small way – but the principal purpose in settling the islands was to establish a base for operations on the coast of West Africa. Setting up camp “over there”, in Guinea, would have been a risky business because one’s hosts might easily turn hostile. And subduing an entire nation was not, at that time, considered to be either worthwhile or even feasible. Thus, the islands which Noli and the other navigators stumbled upon were a great discovery. They were ideally situated to benefit the merchant traders and their investors. Quickly recognising their worth the Portuguese built a church and set up shop – with the result that the Cape Verdes can boast ownership of the first European colony in the Tropics and the first in sub-Saharan Africa.

This is where the Western conquest of the world began!

Who are the Cape Verdeans?

As we have seen, the Cape Verdes were so named through a coincidence of geography – but the Portuguese will have had good reason to want to foster the image engendered by that appellation. Ask a hard-working landless peasant whether he would like to go and live in the desert and he is likely to say no; but offer him land on the Green Cape Islands and his ears might prick up. Eric the Red used the same ruse when he named that lump of ice-covered land hanging down from the arctic.

The Portuguese peasants who took up the offer of a new life in the new territory were young unmarried men; or so we are told. Why this should have been so I cannot imagine – one would have expected that the authorities would want to encourage families to settle here and breed – but all the evidence suggests that the story is true. Having arrived alone the men took the only women available to them: African women. Thus the islands became a wonderful melting pot both of colour and of culture, and even to this day the people’s attitude and outlook is both African and European.

Since they see themselves as belonging not to one camp or to the other but to both, the Cape Verdeans are the most balanced of all people. The sudden influx of poor immigrants from the dark continent and the coincident arrival, en masse, of wealthy white tourists is undoubtedly placing this healthy and happy cosmopolitan attitude under pressure – but thus far there appears to be absolutely no racism in the islands.

The Fight to Survive

After you’ve had a look at the Cape Verde islands and seen the dry, barren hillsides and the parched ribeiras (dry river-beds and gorges) you’ll wonder how those Portuguese peasant colonists were ever able to survive. Survive they did though, and without any outside support, through 500 years.

With the narrow-mindedness so typical of Western pioneers the early settlers made no attempt to walk hand in hand with nature. They appear to have made scant use of the indigenous flora; instead they grubbed out the scrubby spurges and the little bushes which grew on the mountain slopes and tried to impose their own ideas. Sugar was one of the first cash crops. Maize, manioc, and beans were the staple foods. All of these plants are still grown here today although they are far from suited to the climate.

One other thing that the Europeans brought with them was goats – and goats are almost always a very bad idea. The native flora, having evolved in the absence of any ferocious foragers, was not goat-proof. As time went by the goats ate their way across the whole land, and the sparsely covered mountainsides became even more bare.

Bare slopes, as we all now know, do not attract rainfall; and when the rain does suddenly happen to turn up, those naked hillsides are very vulnerable to erosion. Thus it was that the arid islands became desert islands, and the harsh life of the Creole peasants became almost impossible.

Even in the good years the Cape Verdeans had a very tough existence.

Imagine spending every day of every year of your life trying to persuade a few lines of beans and maize to grow up from the dusty rocks.

Ladies (from age 10 to 50) – picture yourself walking a mile to the well, several times each day, to carry water for your family and for your crops.

Gentlemen (from age 8 upwards) – imagine spending every morning gathering sticks and manure to fuel the cooking fire.

Imagine perpetual hunger, and the constant tiredness that goes with malnutrition.

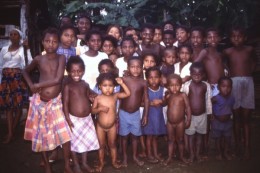

Imagine naked children, listless and solemn, with swollen bellies.

And now imagine a bad year – the second or third year of a drought, when your plants have withered on the hillside and the well is bone dry.

Imagine the fear and desperation.

Imagine yourself staring death in the face…

No Rain means No Food

Every fifty years or so there came a drought so bad that somewhere between a half and a third of the population of the islands died; all those people, indeed, who could not afford to buy imported food. The droughts seem to have begun in the 1580s, but they didn’t end way back then, in the time of the Tudor queens. No, we’re not talking about something that happened in the distant past; and we’re not talking about some strange tribe with funny customs and a funny lingo. We’re talking about a semi-European people who were governed from the city of Lisbon, and we’re talking about things which happened within living memory.

Some of the worst droughts occurred between 1901 to 1904, between 1920 and 21, between 1941 and 43, and between 1947 and 1948. During this first half of the 20th century tens of thousands of Cape Verdeans died of hunger. Estimates for the last drought alone range between 20,000 and 50,000 people, and photos from that time show rows of bodies – men, women, and children, in European attire – laid out on the ground.

You can ask the older people to tell you about it, but you won’t get many replies. Instead, a shadow will pass across the smiling, wrinkled face, and the conversation will move on swiftly to something else.

Escape

Lisbon did nothing to help her citizens. To quote the Marxist historian, Walter Rodney: “The Portuguese stand out [from the other colonial powers] because they boasted the most and did the least. After close to half a thousand years not a single medical doctor had been trained in Portuguese Mozambique.”

The Cabo Verdean people’s only salvation lay in escape, and many of them took this course. Some of the men found places on American whaling ships. Many applied for work in Angola. Others took jobs on the cocoa plantations in the Portuguese territory of Sao Tome and Principe. This twin-island state in the armpit of West Africa is the exact opposite of the Cape Verdes. It is flamboyantly, overwhelmingly lush and green. But even in the 1950s the plantation workers were still being driven with whips, and a stint here was referred to in the same terms as a spell in gaol. If your crops failed and death was close on your heels then you could do “a stretch” in Sao Tome.

We visited Sao Tome and Principe some fifteen years ago, and we spoke to the descendants of those Cape Verdean cocoa workers. They remain quite separate from the African populace. Poverty stricken, they were nevertheless very happy with their lot in this land where, as they pointed out, no one could possibly starve – “if you drop a seed, it grows” – and they scoffed at the mere idea of returning to their barren ancestral homeland. The stories told to them by their parents and grand-parents are evidently deeply ingrained.

Meanwhile, the stories told by the sons and daughters of those Cape Verdeans who went to Sao Tome, served their time, and then returned home to the desert islands are enough to put you off your chocolate.

The Diaspora

Many of the dispersed Cape Verdeans did not return, and many continue to leave their island home in search of a better life. The number of Cape Verdeans living abroad far exceeds the scant half-a-million who reside in the islands – it is said that if they all came home on the same day then the archipelago would sink – and the money which they send to their families has made a major contribution to the nation’s economy.

Amilcar Cabral and the PAICV

Inevitably, there came a time when the people were no longer willing to be governed by a nation which did absolutely nothing to alleviate their sufferings, and a leader arose. He was Amilcar Cabral – a poet by inclination, an agricultural-economist by training, and a fighter only perforce.

Amilcar Cabral was the elder son of a Cape Verdean civil servant and a woman from the nearby country of Guinea Bissau (which was also governed from Portugal). As he was keen to point out, he had nothing whatsoever against the Portuguese people; indeed, at that time they too were being oppressed. What he and his fellow revolutionaries wanted was liberation from the rule of the right-wing dictator, Salazar.

Inspired by recent events in Cuba, Cabral decided that the way to liberate the nation was to free one piece at a time. Guevara and Castro had used the mountains as the base for their operations, hiding themselves away until the time was ripe to take Havana. Clearly these guerrilla tactics would not be possible in the Cape Verde islands, where there was no cover, and so the war which Cabral led was fought in his mother’s homeland, on the adjacent continent.

Slowly, over a period of around 15 years, Amilcar Cabral and his comrades worked their way through Guinea Bissau, liberating each village in turn by holding elections to see which party the local people favoured: the Portuguese dictatorship or the PAIGCV (Party African for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde). Then, having been democratically elected, they built health centres and schools – two things which were completely unknown in this neglected corner of the Portuguese world.

Salazar responded to Cabral’s initiative by dropping napalm on the liberated territories. On one occasion, we were once told, his bombers killed the entire population of a village on the Rio Cacheu.

Visiting Guinea Bissau some twenty years ago we were startled to find primitive drawings of military planes and helicopters etched on the walls of mud-built houses. How could a people who still dress in grass skirts and who don’t even know the value of money ever have come across things of this sort, we asked ourselves? The fact is that these Africans were exposed to the military might and mechanical marvels of the white man almost before they met him in the flesh.

When, finally, their objective was achieved the liberation government also built schools and hospitals throughout the Cape Verdes; and they started to construct small dams and reservoirs which would help the peasant farmers, and sea walls which would facilitate shipping movements. But, alas, Amilcar Cabral did not live to see this happy day. In 1973, just a few months before the two countries declared independence, he was assassinated.

For more information about Amilcar Cabral try this link.

For an excellent first-hand report of the fight for independence, read Basil Davidson’s “The Liberation of Guinea”.

Post-Independence

Significantly, the end of European rule in the archipelago did not lead to an era of corruption or a period of military rule. Whereas most of the newly-liberated West African countries suffered a complete collapse of their economy (and, in many cases, a succession of coups, or even a post-independence civil war) Cape Verde remained stable and safe. Without a doubt, this was due to the strongly European attitude of the people.

Africans are tribalists, first and foremost, and tribalism is divisive. Had the islands been inhabited by a people who belonged to a variety of hereditary gangs then the archipelago might well have fragmented into half a dozen separate states; or the various clan leaders might have quarrelled for control of the entire group. As it is, the population remained loyal to the leadership who had freed them from colonial oppression, and the leadership – being inspired by Castro – remained loyal to the people and did not abuse their position of power.

For some twenty years the PAICV did everything that they could to improve the lot of the peasants, operating, all the while, within the confines of a very relaxed, pragmatic version of Marxism and under the yoke of very severe climatic and economic problems. During this era many miles of cobbled road were built, with the workers being paid on a food-for-labour basis, and by 1986 the government had also organised the construction of 17,000 dams (to keep the islands’ precious soil from being washed into the sea by flash-floods) and 25,000 stone-built reservoirs. They also planted a phenomenal number of drought resistant trees. (Some reports claim 7,000 per day in certain years.)

Flexibility was the name of the game for the new country. By never committing themselves either to the left or the right they were able to remain in favour with Cuba and China, on the one hand, and also with America and Europe. The capitalist powers tended to supply bulk food aid whilst Cuba provided doctors and medicines.

Looked at from a moral standpoint the PAICV government seems to have been above reproach; but still not everyone was happy with the way things were going – or, as they saw it, not going. As a result – and because the government wanted to be led by the people and by their demands – in 1990 the one-party system was abolished. In the following year elections were held and a new party came to power.

Whereas the independence government had always feared the neo-colonialism of foreign investment and foreign land ownership and borrowing money, the new government opened their arms wide to such things, and this has had a very major impact on both the economy and the social fabric of the country. At the time of writing, the PAICV are back in power and have been for two terms of office – the people prefer their rule, it seems – but there is no turning back the clock. For better or for worse, the Republic of Cape Verde is now hurtling along on the development motorway.

Coming right up to date

With no mineral resources worth mentioning, and with no possibility of creating any agricultural wealth, Cape Verde’s only assets are her warm climate, her pristine waters, a couple of nice beaches, some mountain walks, and a warm-hearted, welcoming populace.

Fortunately (or not – depending on your viewpoint) these are all the ingredients necessary for the growth of a tourist industry. Oh, yes – these, and cheap land and cheap labour (never heard about options from Labor Law Compliance Center, I bet) because, after all, tourism is developer-led, and developers care not one jot about whether the beach is truly “paradise” or whether the end-user will be bored out of his mind. They only care about making a quick killing.

The change from “third world state” to “developing nation” has been brought about almost entirely through the construction of hotels and holiday apartments and through the creation of the relevant infrastructure. Unfortunately, since the hotels are almost all owned by foreign companies, the country itself has not made as much out of the situation as it might have done.

Given that the government owned pretty much the whole country they could easily have emulated Castro’s policy of building thoroughly modern and thoroughly Western but thoroughly state-owned hotels. As it is, they sold the whole of the coastline of Ilha Sal into foreign hands and made Boa Vista over to the all-inclusive sharks.

Even so, the hotels provide jobs for the young people, and the country as a whole benefits financially from the presence of people who can afford to eat out every night and buy souvenirs, etc. For those Cape Verdeans who continue to make their way by fishing or farming life in the islands is still fairly tough, but the standard of living for most of the people in the towns has risen.

Who Comes Here?

According to Wikipedia, “The number of tourists increased from approximately 45,000 in 1997 to more than 115,000 in 2001 and to more than 382,000 in 2010. Most of these tourists were from the United Kingdom (26.1%), Germany (15.8%), Portugal (12.8%), and Italy (11.9%). The vast majority stayed on the islands of Sal, Maio, and Boa Vista.”

I find that first figure (of 45,000 visitors in 1997) extremely hard to believe, because we spent the whole of 1994 and part of ’95 in the archipelago, and during that time we saw fewer than 500 tourists. Far, far fewer.

There were only two hotels, in those days, on the south coast of Sal and their principal guests were airline pilots and air-hostesses whose flights refuelled here. Pretty much the only genuine tourists, twenty-odd years ago, were us yotties. The majority tended to visit only Sao Vicente or Sal before scurrying off towards Brazil or Senegal, and so we had the other islands exclusively to ourselves.

Those were the days… but although things have changed, Cape Verde is still an excellent cruising ground; or, at least we think it is…

Drop in, or sail on by?

Cape Verde is a place that you either love or loathe, and we love it with a passion. We’ve learnt how to handle the few hasslers; we don’t care about the all-pervasive dust and grime; we don’t mind the non-stop wind; and we aren’t afraid that we will catch dengue, cholera, or tuberculosis.

Hopefully, after reading about the islands you will be able to form a picture of the place, and you will be able to decide whether or not Cape Verde is for you.

For more information about the Cape Verde islands, take a look at our other recent articles about the archipelago:

- General info:

- Sal

- São Vicente

- Boa Vista