Cape Verde – Sal – What to do in Sal

Cruising notes given in good faith, but not to be taken as gospel.

Having cleared into the island, in Palmeira, where should the visitor to Sal go next?

Well, some people would say that he might as well move on, straight away – to Boa Vista, or to Sao Nicolau and then Sao Vicente…

There is a certain amount to be said for this philosophy. However, Sal does have a little bit more to offer. If you want to get to know the place a little better then you need to move on from the down at heel village in the island’s expanding commercial port and take a look at her other face.

Ports and Anchorages

So – what other anchorages are there in Sal?

The RCC’s Atlantic Islands cruising guide mentions a small port on the east coast of the island: Pedra da Lume (properly spelled, Pedra do Lume).

Well… you can imagine what an east coast port would be like in the average tradewind conditions. In July or August, when the swells are down and the wind is usually light, then this place might provide an interesting overnight anchorage – but then so might a couple of the other bays and beaches to the north and south.

The port of Pedra do Lume was built to enable small barges – little bigger than the local fishing boats – to come alongside and take on a load of salt which they then ferried out to trading ships lying at anchor. If your yacht is a small centreboarder and draws less than one metre then you might get inside, if conditions are good… but before you try you should take a bus from Palmeira to Espargos, and take a taxi from there (or else walk), and check the place out.

Indeed, a visit to Pedra do Lume is well worth anybody’s time and money. (More details of the place are given below.)

I think that Pedra do Lume is the only port in the Cape Verdes that we have not yet managed to anchor off, conditions when we are in the vicinity never having been appropriate.

There are a couple of bays on the west coast of Sal which make ideal anchorages but for some reason the local police don’t seem to like anybody using them anymore; and now that they have a boat they are apt to chase people away.

The only other approved anchorage is Santa Maria, a village-come-holiday resort on the south coast. Here the visitor discovers the new-look Sal.

Santa Maria

Santa Maria began its life as the depot for a nearby salterns. The salt harvested from the pans was stored in a tall, rather elegant warehouse standing on the foreshore and when ships arrived to take it away it was trucked along a rustic quay, immediately opposite the warehouse, and was ferried out to the ships in small wooden barges.

The warehouse has been restored and extended and is now home to a small restaurant and a couple of souvenir shops; and the quay is still standing, too. Indeed, at the time of writing it is in a pretty good state of repair. This is just as well because it there is no other place, on this coast, where one can get ashore without swimming.

Visitors should anchor immediately to the south west of the wooden quay, amongst the fishing boats and charter yachts. The nearer you get to the beach, the shorter the row to the quay – and the more you will roll. When the swells are really big the waves sometimes begin breaking parallel with the end of the quay; so don’t try sneaking in any closer than that.

In the winter, when the swells often creep around the island, getting onto the old wooden quay can be a bit of an adventure – but not so much of an adventure as trying to land on the beach. At this time of year the beach is popular with kitesurfers and surfers.

For some reason there is only one ladder, fitted to the south-west corner of the quay. 17 years ago it was an antique affair which swung to and fro. Getting onto it while the dinghy surged back and forth was no fun at all; not if you happened to be carrying a toddler on your hip.

The new ladder is well-secured and it is made from stainless steel – which is alarmingly slippery when wet.

Being the only point of access between the land and the sea, the old quay is a busy place. The fishermen come alongside, as best they can, to land their catch. Then they clean their fish on the planks, covering them in guts and gore.

More to the point, the fishermen are apt to leave their dinghies tied to that same corner of the quay.

It isn’t possible to tie the boats onto the other corner of the quay, or onto the end, because this is the territory of the anglers, with their rods. (It was ever thus: even 17 years ago, when the local boys could only dream of owning a rod, they dangled their hand-lines from the end of the quay, and the men had to keep their boats clear.) And it isn’t possible to tie the boats on the other side of the ladder, closer to the shore, because the breaking swells might easily swamp them. We once saw a swell break at the head of the jetty and come splashing up through the wooden planks; and that was not on a particularly “big” day.

So – when you go ashore in Santa Maria you will tie your dinghy to the corner of the quay; and when you return you will lie down on the jetty, amongst the gore and guts, and unravel your painter from amongst the maypole plait of other people’s lines.

Note, too, that not every fisherman has his own dinghy. When they want to get out to their boats the men use whatever is available. This is accepted practice here and visitors such as you or I just have to lump it if the dinghy is temporarily absent or is found to be rather wetter than when it was left.

A Sleepy Village Grows Up

17 years ago Santa Maria was probably as quiet, or even quieter than when it was a salt depot. There were just two short cobbled roads, with two lines of small cottages facing each other, and almost no traffic disturbed the dust which lay between the stones.

The praҫa (village square) looked onto the sea. The baker gave us the traditional baker’s dozen when we went to buy bread rolls. A couple of women sat in the gutter selling papayas and dried beans.

And that was that.

There were no shops.

Now… Now…! Now we don’t recognise the place.

The old salt warehouse is still there, as I have said, but the truck rails which ran from the warehouse towards the old wooden jetty have been buried under a nice new cobble-stone covering.

The view from the praҫa is blocked by a line of hotels and apartments.

The baker has gone upmarket and opened a cafe, with squeaky clean floors and a flat-screen television hanging on the wall.

There are new roads, and new glitzy buildings, and to the east of the village there’s a whole new district of ugly modern apartments which is encroaching into the desert.

There are so many cars in Santa Maria nowadays that you have to use the highway code to cross the street. And those old cottages have all been turned into gift shops selling tacky Senegalese wood carvings and expensive T shirts.

There are so many cars in Santa Maria nowadays that you have to use the highway code to cross the street. And those old cottages have all been turned into gift shops selling tacky Senegalese wood carvings and expensive T shirts.

There are a couple of very small supermarkets in the village now, but prices here are even steeper than in Espargos. And that goes for the veg being sold by the street-vendors too: it’s outrageously over-priced and it’s of very poor quality.

17 years ago there were two hotels in the village: the old ropey one belonging to Aeroflot (the Russian airline) and a rather fancy newer one – the Morabeza – which served the needs of the South African pilots.

The Morabeza is still the best looking and best sited hotel in Santa Maria, but it is now only one of perhaps a dozen establishments; and there are more under construction.

Besides the hotels lining the beach in Santa Maria there are also a couple of large and very unsightly holiday-home developments standing to the north of the village, on the west coast, and although they appear to be completely neglected and are falling into disrepair more developments are planned. Indeed, as has been mentioned elsewhere in these pages, we hear that planning permission has been given to carpet the whole of the desert, on that side of the island, in concrete and tarmac. I guess there are still plenty of people eager to hand over their money on the promise of doubling their investment, but I wonder how far the ball can roll.

Gazing across the island, from the east coast, I found myself thinking of a time when the shabby windswept apartments – already reminiscent of a maximum security prison – are nothing more than bleak ruins haunted by dust-devils and drifting sand.

Sight-Seeing in Sal

So, what does a holiday-maker do in Sal?

The place is ugly, wind-swept, and entirely lacking in the sort of amenities that most Western tourists require, so what do the thousands of tourists who come here do with themselves all day and night?

Day 1 – Lie on the white sand beach, enjoying the sun but wishing it weren’t quite so windy.

Day 2 – Take a guided tour of the island, visiting the Palmeira, Espargos, and the salinhas.

Day 3 – Pace up and down the beach; swim a bit, though it isn’t very warm; eat some seafood; try to find somewhere to spend the evening…

Day 4 – Sod the expense: take a ride on a charter yacht.

Day 5 – Cripes! Is it really only Day 5….

Palmeira we have already discussed.

Espargos – the island capital – used to be a very sleepy little hole with nothing to see or do and nothing much to recommend it. Now, it’s a sleepy fairly-little hole with one brand-new road, on the eastern side of town, boasting some wholly uninteresting buildings and shops. At the far end of that road lies a rapidly expanding African quarter which accommodates immigrants from the continent. There’s still nothing to see or do here, and the place still has nothing much to recommend it to the passing tourist.

If you need a post office or an internet cafe, you can find them here, and there are also two or three banks, each one with an ATM / hole-in-the-wall machine accepting Visa credit and debit cards. There are also various small bars and cafes; there’s a very small vegetable market; and there are a couple of supermarkets. Prices here are a lot higher than in the Canary Islands and, indeed, a lot higher than in Praia, Sao Vicente, or even Sao Nicolau. Somebody is making big bucks importing food into the island from Mindelo!

The salinhas – or salterns – are the only venue in Sal that are worthy of an expedition in a hire car or a taxi. There are actually two of them, one lying on the outskirts of Santa Maria and the other at Pedra do Lume.

The salterns outside Santa Maria are not on anybody else’s list, I have to say, but I found them interesting and quite attractive. The ones at Pedra do Lume are on every tour guide’s itinerary. The difference lies in the location. The pans at Santa Maria lie surrounded by the desert whereas the ones at Pedra do Lume are hidden inside a volcanic crater and the only access is via a short tunnel in the rim of the crater.

The pans are still being worked, in a desultory sort of a fashion, and you can wander in and take a look at acres of white salt glistening like snow. But nowadays you have to pay for the privilege; and – alas – your money does not go to the Cape Verdeans; it goes to an Italian owner who was sold this – the only piece of heritage on the entire island – with the approval of the government!

[The name Pedra do Lume is spelled in a variety of ways by the locals. The standard of literacy is not high, in these parts; and in any event, in the ancient of days – when the villages were founded and the charts were made – spelling will have been an arbitrary matter. This leaves us with an interesting question: Pedra means rock. Pedro – which you will sometimes also see in use – means Peter. So, which did ye olde settlers mean?

Lume is a rather archaic word meaning a spark or glimmer of light; and do and da – both of which we have seen applied here – mean “of the”. Well, we can soon sort that one out: Lume is a masculine noun – so the preceding “of the” has to be de o – which is abbreviated to do.

This leaves us with the possibility of either Peter of the (very faint) light, or the rock with the (faint) light. Myself, I think that the place was probably named for a feeble lighthouse – not much more than an oil lamp, perhaps – which was lit on the headland (rock) for the benefit of ships arriving to take off salt.]

After you’ve visited Pedra do Lume, watched the fishermen landing their catch in Palmeira, and eaten cachupa (maize stew) in a bar in Espargos then you’ve seen and done everything that there is to see and do in Sal – unless, of course, you’re a diver or a kitesurfer.

Kitesurfing in Sal

If you’re a kite-surfer it’s a different story. You can forget everything that has been said about the ugly desert landscape and the lack of amenities. If you’re a kitesurfer, Sal is paradise.

From December to March the wind almost never fails to go blasting across Sal, and when the swells roll in, from storms in the higher latitudes, there are some excellent breaks around the island. The one-time kitesurfing world champion, Mito Monteiro, lives in Santa Maria, and there are four kitesurfing schools (LINK to Rox article)on the beach adjacent to the village.

While we were in Sal we met the crew of Best Odyssey, a charter catamaran which has been making its way slowly around the world visiting all the best kitesurfing locations; and they seem to have rated Sal as unbeatable:

“We spent over two months anchored off Sal, which on first inspection is just plain ugly. Flat, windswept, and brown. But living off her coasts on a beautiful boat with a plethora of toys, catching more waves than you’ve ever dreamed of and, well, Sal starts to look pretty incredible.”

During their four month stay in the Cape Verdes the crew of Best Odyssey either surfed or kite-surfed almost every day. “The only days we didn’t were because we were either too lazy, or had to prepare the boat for another trip.” They also liked the lack of crowds – sometimes, they found, they had even the most famous breaks entirely to themselves – but the very best thing, so far as the skipper of the catamaran was concerned, was the predictability of the place: “Knowing that this or that surf-break would be working, knowing the wind would arrive, knowing I could keep our guests in smiles” – these comforts made Sal the nearest thing to paradise.

Their website features some great pictures, including one of a guest kitesurfing across the shallow waters on the edge of the Pedra do Lume saltpans.

Diving

If you’re a diver then you’ll also enjoy Sal, because the sea-life around the Cape Verdes is still relatively abundant with a wide variety of fish, green turtles, and lots of sharks. There are now plenty of diving centres in Santa Maria.

If you don’t like diving but you want to see sharks you can actually paddle with them, on Sal’s east coast…!

Obviously, if you support the locals to the extent of buying sharky souvenirs (such as mounted jaws) then you give them a good reason to kill sharks and you make the survival of these animals in this neighbourhood even less likely. (While we’re on this subject – Cape Verdean and Senegalese vendors often offer puffer-fish skins for sale. They are pretty impressive, but this fish is said to be on the decline; so, once again, we do better not to support this little industry.)

Hiking

Forget it; you’re on the wrong island.

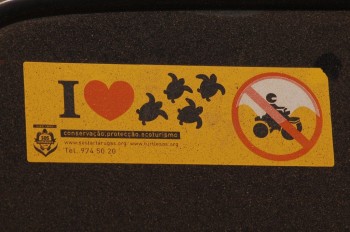

Quad-biking

Bored tourists who can find nothing else to do often hire a quad bike. If you do this, please don’t drive on the beach; keep to the desert dirt. Quad bikes driving on the beach crush and kill the unhatched turtles whose eggs are laid in the sand.

Finally, one of the best ways to amuse yourself whilst on holiday in Sal is to leave; get on a boat and pay a visit to the neighbouring island of Boa Vista, for example.

Mind you, if it’s your own boat, and if you are visiting the islands during the winter months, then I would suggest that you go anywhere other than Boa Vista; because Boa Vista, in the winter months when the swells are rolling down from the north, is pretty much untenable.

But that’s another story, to be told on another day.

For more information about the Cape Verde islands, take a look at our other recent articles about the archipelago:

- General info:

- Sal

- São Vicente

- Boa Vista